Higher Eduction

Objective

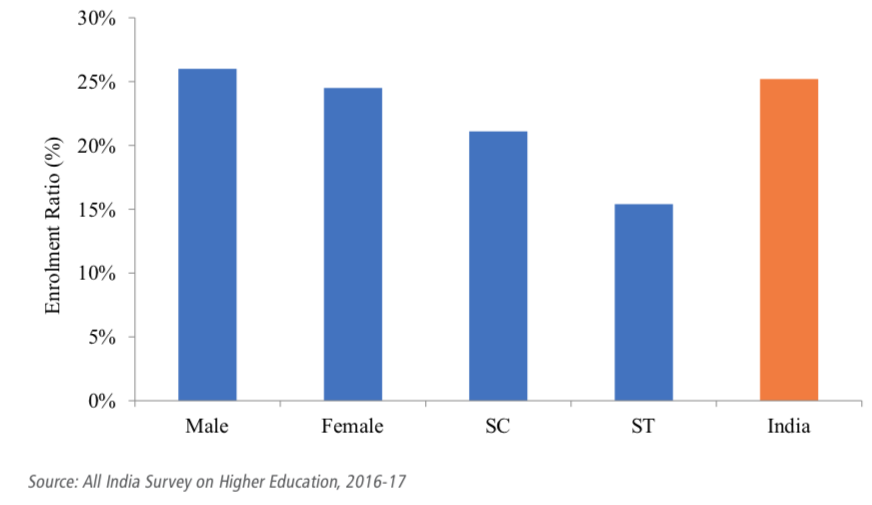

Increase the gross enrolment ratio (GER) in higher education from 25 per cent in 2016-17 to 35 per cent by 2022-23.

Make higher education more inclusive for the most vulnerable groups.

Adopt accreditation as a mandatory quality assurance framework and have multiple highly reputed accreditation agencies for facilitating the process.

Create an enabling ecosystem to enhance the spirit of research and innovation.

Improve employability of students completing their higher education.

Current Situation

India has 864 university-level institutions, 40,026 colleges and 11,669 stand-alone institutions. The number of university-level institutions has grown by about 25 per cent and the number of colleges by about 13 per cent in the last five years. The private sector accounts for a large share of these institutions, managing 36.2 per cent of universities, 77.8 per cent of colleges and 76 per cent of stand- alone institutions in 2016-17.

India’s higher education GER (calculated for the age group, 18-23 years) increased from 11.5 per cent in 2005-06 to 25.2 per cent in 2016-17. However, we lag behind the world average of 33 per cent and that of comparable economies, such as Brazil (46 per cent), Russia (78 per cent) and China (30 per cent). Korea has a higher education GER of over 93 per cent.

In addition, regional and social disparities continue to exist in higher education: GER varies from 5.5 per cent in Daman & Diu to 56.1 per cent in Chandigarh. Figure 24.1 indicates GER in terms of gender and social groups. GER is 26.0 per cent for males and 24.5 per cent for females, with females constituting 46.8 per cent of the total enrolment of 35.7 million. While the GERs for scheduled castes (SCs), scheduled tribes (STs), other backward castes (OBCs) and minorities have been increasing, these are still below the overall average in most cases.

Quality is a challenge in higher education in India. Few Indian institutions feature in the top 200 in world rankings. In comparison, China has seven universities in the top 150 (3 in top 50) of the Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) world rankings. These rankings did rank three IITs and the IISc amongst the top 20 BRICS universities in 2018. Another issue is the employability of graduates.

Recognising the need to improve access, equity and excellence in higher education in the country, the government has taken significant steps, including the following:

- Implementation and continuation of the centrally sponsored scheme,

Rashtriya Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan (RUSA): This scheme seeks to improve access, equity and quality in state higher education institutions through a reforms-based approach and links funding to performance.4 The continuation of RUSA was recently approved until March 2020 with an almost three-fold increase in allocation compared to that in its first phase (2013-17). The second phase of RUSA puts a premium on quality enhancement and addresses concerns of access and equity in the aspirational districts identified by the NITI Aayog.

Figure 24.1: Gross enrolment ratio in higher education, 2016-17

Note: Image taken from Niti Aayog - Strategy for New India@75 Document

Note: Image taken from Niti Aayog - Strategy for New India@75 Document

National assessment and accreditation reforms: While making accreditation of higher education institutions mandatory, the reforms move away from an intrusive system to a more enabling, mixed method of assessment and accreditation. The process of accreditation has been fast-tracked and made more transparent. The emphasis is more on self-assessment, data capture, validation by third party evaluation and objective peer review. This is a paradigm shift from the subjective assessment parameters adopted earlier. Ongoing reforms could lead to the empanelment of multiple accreditation agencies.

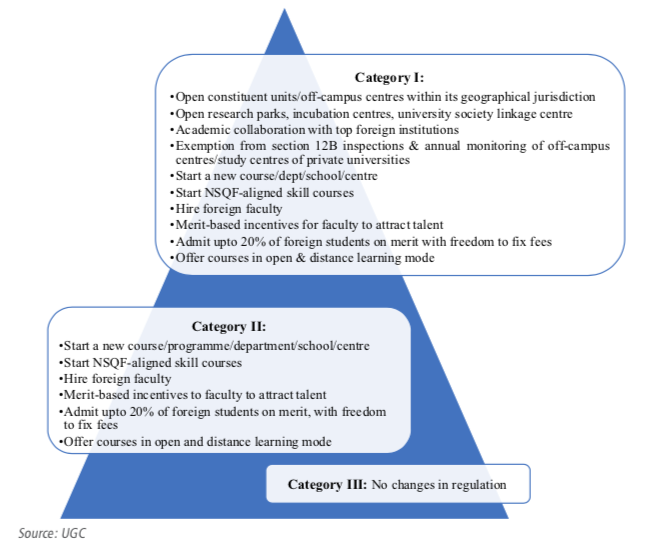

Regulations for graded autonomy to universities and autonomous colleges: A three- tiered graded autonomy regulatory system has been initiated, with the categorization of institutions as per their accreditation score by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) or other empanelled accreditation agencies, or by their presence in reputed world rankings. Category I and Category II universities will have significant autonomy as shown in Figure 24.2. Similarly, the University Grants Commission (UGC) has also issued new regulations for granting autonomy based on accreditation scores for colleges. These colleges will have the freedom to conduct examinations, prescribe evaluation systems and even announce results but are not allowed to grant degrees.

Figure 24.2: UGC’s graded autonomy regulations for universities

Note: Image taken from Niti Aayog - Strategy for New India@75 Document

Note: Image taken from Niti Aayog - Strategy for New India@75 Document

Constraints

Outdated and multiple regulatory mechanisms limit innovation and progressive change.

Outdated curriculum results in a mismatch between education and job market requirements, dampens students’ creativity and hampers the development of their analytical abilities.

Quality assurance or accreditation mechanisms are inadequate.

There is no policy framework for participation of foreign universities in higher education.

There is no overarching funding body to promote and encourage research and innovation.

Public funding in the sector remains inadequate.

There are a large number of faculty posts lying vacant, for example in central universities, nearly 33 per cent of teacher posts were vacant in March 2018; faculty training is inadequate.

Way Forward

1. Regulatory and governance reforms

Provide Legislative Backing

Ensure effective coordination of roles of different higher education regulators, such as the UGC, All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) and National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE), and restructure or merge these where needed.

Amend the UGC Act to provide legislative backing to the tiered regulatory structure.

Create a framework to allow foreign universities of global repute to operate in India, in collaboration with Indian institutions to offer joint degree programmes.

Ensure that the selection process of Vice-Chancellors of universities is transparent and objective.

Link at least a proportion of the grants to performance and quality.

2. Curriculum design

Freedom to Innovate and Expand Curriculum

Domain experts in each educational field should be asked to develop a basic minimum standard in curriculum that will serve as a benchmark for institutions at the undergraduate and post-graduate levels. Institutions should be given the freedom to innovate and expand curriculum beyond this basic minimum standard. Curriculum and pedagogy at all higher education institutions should be updated continuously through mandatory feedback from domain experts, faculty, students, industry, and alumni.

Diverse post-secondary career options should be provided through skills/vocational training that should be integrated seamlessly with higher education and the skilling mission.

Internships by students in undergraduate courses should be encouraged and potentially mandated in all professional and technical courses. This would help with the practical orientation of students.

3. Reforming accreditation framework

Accreditation of Institutions

- All higher education institutions must be compulsorily and regularly accredited. Despite a two-fold increase in accreditation levels in the last five years, accreditation coverage is still inadequate. One way to bridge this gap by 2022-23 is to allow credible accreditation agencies, empanelled through a transparent, high quality process, to provide accreditation. Accreditation must give adequate weightage to outcomes rather than inputs only. Public information material brought out by institutions and their websites should prominently display the accreditation status and grade.

4. Creating ‘world class universities’

Institutions of Eminence

- Twenty universities – 10 each from the public and private sector – are being selected as ‘Institutions of Eminence’ and are helping to attain world-class standards of teaching and research. The funding of INR 1,000 crore over a 5-year period to each institution, planned for selected public universities, could be further increased. Further, a graded mechanism to ensure additional funds flow to the top public universities should be developed. This is similar to the model adopted by Singapore and China to develop their top two public universities.

5. Performance-linked funding and incentives

Performance Linked Funding

Only two out of 47 central universities have NAAC scores of above 3.51, despite generous funding available to them. An evaluation may be undertaken to understand the challenges faced by these central universities, and they should be asked to develop strategic plans for getting into the top 500 of global universities rankings in the next 10 years.

Going forward, funding to these institutions should be linked to performance and outcomes through the Ministry of Human Resource Development and the newly constituted Higher Education Funding Agency.

RUSA may be continued beyond March 2020, subject to a credible third-party evaluation. This reforms-based scheme has already made significant headway in getting state public education institutions into the mainstream. Continued support, linked to performance, will go a long way in pushing some of India’s leading state public universities up the ranking ladder.

6. Development of teacher resources

Ecosystem for Deserving Talent is Hired and Retained

Develop stringent norms for faculty recruitment in universities and colleges. A rigorous and transparent process of identifying the best talent for the higher education sector should be put in place. An ecosystem should be created where the most deserving talent is hired and retained. This should include eligibility tests of a high standard, such as existing UGC- recognised NET, as a minimum eligibility criterion for faculty recruitment, to ensure recruitment of candidates with academic and/ or research aptitude.

Quality teaching skills are in short supply across disciplines. A central scheme may be launched to attract teachers of Indian origin.

Enable and encourage the recruitment of practitioners with distinguished experience from professional bodies/industry as faculty.

This can be achieved through the creation of a separate parallel track, on which the mandatory Ph.D qualification for faculty may be relaxed. These industry practitioners may also be encouraged to join as adjunct faculty in the higher education institutions.

Introduce pre-service faculty training (3-6 months), including faculty exposure to the latest tools/techniques of quality teaching and research. Continuous faculty training and updating process should be introduced and made mandatory.

Develop a system of outcome-based faculty evaluation in higher education, which is flexible across different categories of institutions.

Conduct regular quality checks of journals, espe- cially those that are used for evaluating faculty on academic performance indicators (APIs).

7. Distance and online education

Massive Open Online Course (MOOCs) & Distant Learning

- There is a need to broaden the scope of Massive Open Online Course (MOOCs) and Open and Distance Learning (ODL) and tap their potential to provide access to quality education beyond geographical boundaries. Universities with high accreditation scores may be permitted to offer online education programmes. In regular courses, technology could be leveraged to overcome faculty shortages.